NWO Indigenous opposition to nuclear waste storage site highlighted in report

Opposition by area Indigenous leaders to the proposed nuclear waste disposal site slated to be built west of Ignace is highlighted in a larger report studying Indigenous nations’ attitudes to the nuclear industry.

The report was co-published between the CEDAR project and the Passamaquoddy Recognition Group (PRGI). CEDAR is a five-year initiative that is studying energy transition in Canada and which is based out of three Canadian universities, including St. Thomas University in Fredericton. PRGI is a not-for-profit that represents the interests of the Peskotomuhkati Nation, which straddles the modern-day border between New Brunswick and Maine.

The report gathered 30 public communications, including resolutions passed, statements on websites, media releases and letters to government officials made public by Indigenous nations in New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario, as well as over 125 documents submitted to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, the report said.

Susan O’Donnell, an adjunct research professor at St. Thomas University and the report’s co-author, said among the data they collected, it shows that “overwhelmingly” First Nations are opposed to both the deep geological repository being proposed for the Revell Lake site between Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation and Ignace, and a proposed near-surface disposal facility for lower-level nuclear waste storage near Ottawa.

“So, it was kind of a mix between the two sites that are currently the two sites where there’s nuclear waste dumps basically being proposed is what we found,” she said in an interview with Newswatch. “We also saw a variety of concerns about the process of how the decisions were made to site these particular proposed waste dumps.”

“A lot of the concern, and certainly this is a concern that’s shared by the Peskotomuhkati Nation, is the process for getting consent for First Nations.”

The Peskotomuhkati Nation’s traditional territory is the site of the Point Lepreau nuclear plant. Its leadership is concerned about the existing waste being stored at the plant, as well as plans to transport it to another site two provinces away, said Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik Chief Hugh Akagi in his foreward to the report.

Here in Northwestern Ontario, researchers gathered communications of opposition from Nishnawbe Aski Nation, the Anishinabek Nation, Grand Council Treaty 3, Fort William First Nation, the Ojibway Nation of Saugeen, Asubpeeschoseewagong (Grassy Narrows First Nation), Lac Seul First Nation, Michipicoten First Nation and Netmizaaggamig Nishnaabeg (Pic Mobert First Nation).

O’Donnell said that doesn’t include two developments that occurred shortly after the research’s completion: a further resolution from Grand Council Treaty 3 declaring, in part, that they continue to support the position that a repository for nuclear waste “will not be developed at any point in the Treaty 3 territory,” and Eagle Lake First Nation’s court challenge.

“Many concerns have been raised about the ‘willing host’ concept and the industry’s process to choose a site for the proposed deep geological repository,” the report said.

Wabigoon Lake Chief Clayton Wetelainen told Newswatch in late November 2024 — after the report’s research was completed — that his community’s willingness is conditional on the project passing Canada’s and his community’s approvals.

Having years’ worth of on-the-record statements collected in one place about First Nations opposition to nuclear energy — including the existing plans to store the highly radioactive waste it produces — is important, O’Donnell said, as stories tend to get reported piece-by-piece and region-by region.

“That’s what we were trying to show, that there’s a lot of interest in this by Indigenous nations — not only in New Brunswick, but in Quebec and Ontario — and we were trying to show the breadth of interest in the nuclear issue and the radioactive waste issue,” she said.

“We think that that’s the main value of the report, that it basically gathers (the issues) together so people can get a sense of the overwhelming interest by First Nations in this issue in those three provinces.” nwonewswatch.com

article website here

Maybe someone should sit the chiefs down and explain to them just how the Ontario power grid works. Where does all of that electricity come from. How much of the ‘dependable’ electricity that flows along all of those power lines come from nuclear, how much comes from hydro, how much comes from natural gas and how much from everything else.

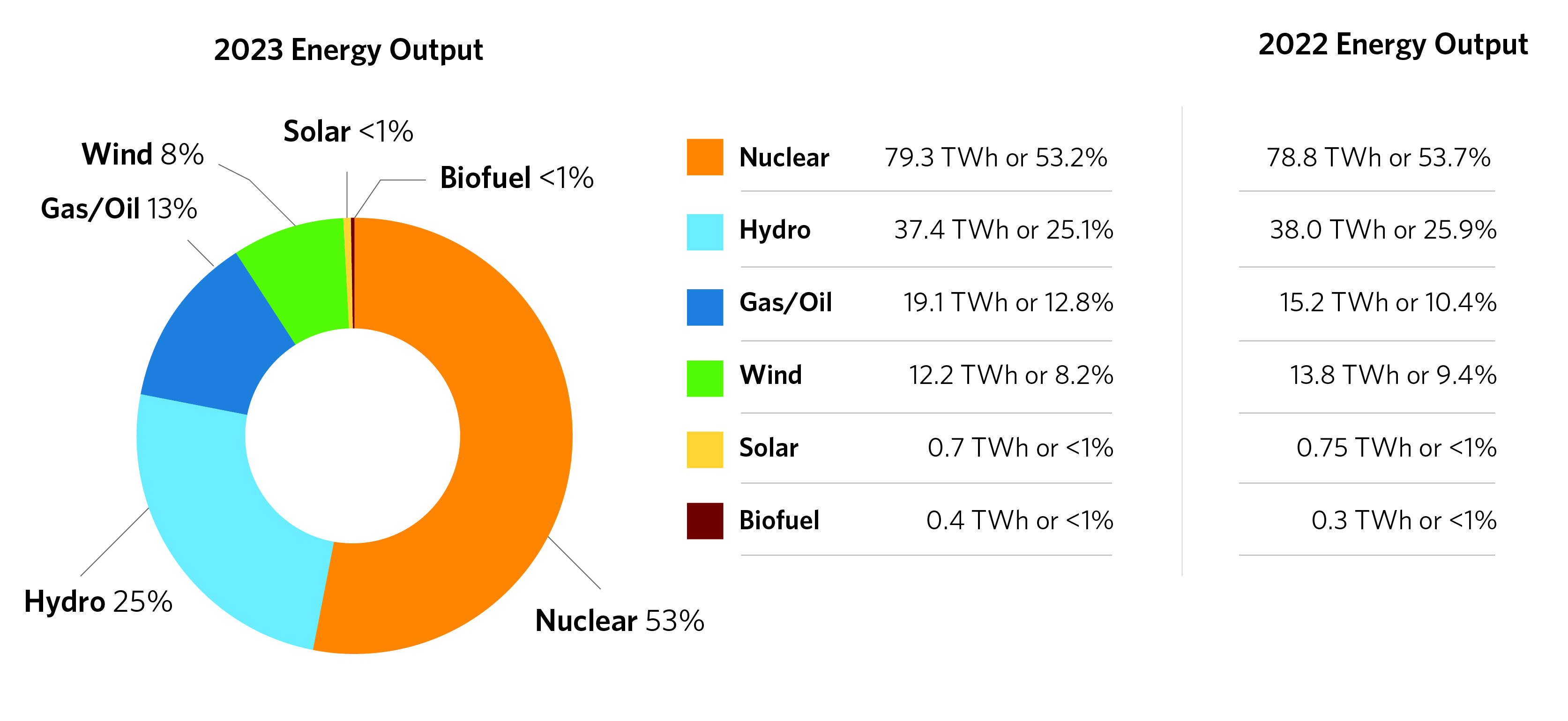

This from Independent Electricity System Operator’s website

What this says is that on any given day, 53% of the electricity being delivered to your home is nuclear generated. That is over half of the electricity in the Province of Ontario.

That includes the electricity flowing up to all of the reserves just connected to the provincial power grid via the Wataynikanyap Power Transmission Project .

Something to consider when opposing a nuclear storage facility. Without dependable sources of electricity, there will be no economic development.

Is hydro dependable? Biofuel? Wind? Solar?

Indigenous-led economic development gathering returns in February

Powerline brings peace of mind in Poplar Hill

Bearskin Lake First Nation added to Wataynikaneyap Power line

Kingfisher Lake First Nation electrifies connection to Wataynikaneyap Power line

Two more northern First Nations celebrate connection to the power grid

Sandy Lake celebrates the arrival of power and light

Wataynlkaneyap Power reaches milestone

Kasabonika Lake is sixth First Nation community connected to grid power

Wunnumin Lake has new houses to go with power connection

Power brings equity among 24 First Nation communities

“Wataynikaneyap Power”

People want electricity. They depend on it. Our entire world depends on a steady stream of electricity. Right now, nuclear is the most dependable source we have. Its the truth.